Picture a flat, dry, dusty grassland with a few scattered trees. Alongside it runs an arrow-straight stream channel. The stream banks are eroded and are falling into the stream. The stream bed itself is a few feet below the top of the bank, and the remains of century-old levees still linger. The tall, dry grass stretches as far as you can see.

Now flash forward a few years, and you’re standing in the same spot, looking upstream. You see a lush, green expanse with willows, cottonwoods, and water everywhere. You’re not sure where exactly the old stream channel is, and several new stream channels now wind lazily throughout the landscape. Honeybees and other pollinators buzz through wildflowers and native plants. Egrets wade in the shallows, and wood ducks paddle in the deeper water. And, come nightfall, you might catch a glimpse of the engineers behind this remarkable transformation: Castor Canadensis, the North American Beaver!

Beavers are native to North America and found throughout the continent, north to south, east to west. They’re known as “ecosystem engineers” – one of the few animals that modify their habitat by creating dams that flood streams. So, when we saw our earlier restoration efforts at Doty Ravine struggling to take effect, we teamed with these little native experts to find a solution — and, as you can see, the results are a resounding success!

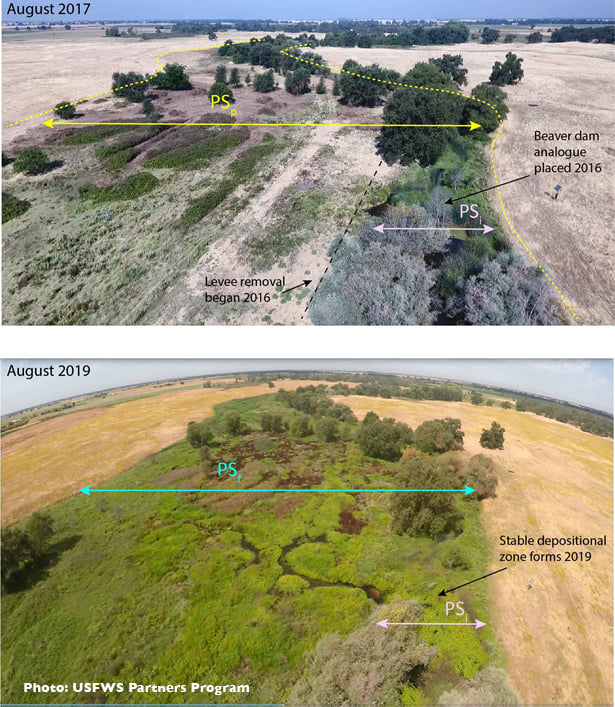

The approach that Placer Land Trust took at Doty Ravine Preserve is called process-based restoration. The idea here is to restore the natural process of flooding across the area where it used to exist, and not say exactly where or what it will look like. Our job was to set up the right natural conditions, then step back and let nature — or in this case, beaver — do the work. To help get it started, we built beaver dam analogues (BDAs), or artificial beaver dams that help give the native beavers the right idea.

We also removed the old levee that was installed to contain the stream and control flooding. We often think of flooding as dangerous and destructive, but floodplains (the flat lands that stretch alongside the stream), are designed to flood — and Doty Ravine Preserve has a lot of floodplain. The traditional approach for agriculture was to drain land so that crops can be planted, and to move water off the land as quickly as possible through a system of straightened stream channel and levees. But with drought, fire, and our changing California climate, it’s important to keep water on the landscape for longer before it flows downstream. The restored floodplain at Doty Ravine acts as a giant sponge, slowing and holding water for a period of time, and providing wildlife habitat, a natural firebreak, and groundwater for the area.

Indigenous cultures have practiced this kind of nature-led stewardship for thousands of years, but modern approaches tend to be much more controlled — an engineer designs how it will look, heavy equipment is used in to carve out the floodplain, and plants are re-planted according to a design plan. That may sound good, but there are some big trade-offs: the survival rate of planted plants in these settings is often low, the work is resource-intensive, and it all has a significant carbon footprint. It also costs a lot more money: potentially hundreds of thousands, or even millions, of dollars. Instead, with process-based restoration, the beavers provided a solution that was both cost-effective and wildly successful — with 60 acres (equivalent to about 45 football fields) of dry floodplain brought back to lush, green, diverse life in just a few years.

So what exactly did the beavers do at Doty Ravine?

They did what they naturally do: built small, wooden dams that slowed the water down and allowed it to spill out onto the floodplain. That also allowed sediment that is naturally carried by the stream to drop out around the areas of the beaver dams and effectively “lift” the artificially deep stream channel. This in turn builds even more connection of the stream channel and floodplain, and so it continues.

Natural beaver dams are very different than typical dams, and do not pose long-term barriers to fish or other species moving upstream. The beaver dams are temporary, meant to move and change, and they sometimes fail or get blown out. It’s very dynamic and totally unlike a typical concrete dam.

What does the preserve look like now? What are the benefits?

This is a fire-prone landscape, and fire is a natural process. Historically there were more frequent but lower intensity fires that the land had adapted to. More recently, however, with increased temperatures, higher fuel loads, less rain and more development, fires have become catastrophic. This project is unlikely to drastically change the wildfire aspect – while it is large for a floodplain on this size stream, it’s still a small area across a large landscape. But it provides benefit as a potential fire break if there is a fire. There once was a fire that moved across this property, and having this large, wet floodplain area certainly would have helped slow it down.

We’re also seeing all kinds of wildlife return to the area, in addition to just the beavers. Juvenile salmon and other fish use the new stream side channels across the floodplain. Many migratory bird species now use this area, and our wildlife cameras have spotted herons, egrets, raccoons, otters, and more. The preserve provides lush, green grazing land for local ranchers, and cattle grazing is carefully managed to coexist with wildlife habitat and restoration.

“To see how quickly the wetlands came back, and with relatively little effort on our part, was amazing,” says PLT Conservation Director Lynnette Batt. “I came into the project mid-way, after the upper 30 acres of floodplain had been restored. However, the lower 30 acres of floodplain was still totally dry and disconnected from the stream. It was really something to see that lower area reactivate, and water return, meandering stream channels, and plants and birds and wildlife. All this returned in a few short years.”

And this style of restoration project is catching on. Even in areas without active beaver populations, humans can adapt beaver techniques to return wetlands to their natural condition. “In the lower floodplain area, more of the work was done by us. We removed portions of the old levees, and installed beaver dam analogues,” says Batt. “The more human-driven restoration on the lower portion was successfully able to mimic the more beaver-driven restoration on the upper portion, and restored that floodplain.”

“We were extremely fortunate to get connected with Damion Ciotti of US Fish and Wildlife Service. He has been the driver of this project for years, and their Partners for Fish and Wildlife Program provided funding,” adds Batt. “This method is gaining a lot of traction, and this site has served as a model and demonstration site for federal trainings on this technique.”

The project also received funding from the California Waterfowl Association through the North American Wetland Conservation Act.

See the Doty Ravine beavers in action:

News coverage of the Doty Ravine Preserve restoration project:

Take A Look At How Beavers Are Vital For Healthy Ecosystems

The Sacramento Bee – July 2, 2021

How a group of beavers prevented a wildfire and saved California a million dollars

The Independent (UK) – July 8, 2021

CBC Radio – As It Happens – California Beavers

Radio-Canada, July 8, 2021 (minutes 39:58)